Key Takeaways

- Early Americans used simple, natural ingredients—soil, plants, and metal scraps—to paint homes, forts, and clothing.

- Each color carried a message: black spoke of humility, red brought warmth, and blue shouted independence.

- Knowing these hues helps historians, designers, and homeowners recreate authentic colonial looks.

- You can match these shades today with safe, low‑VOC historic paints or DIY natural dyes.

- Learning the story behind each color adds depth to restoration, decor, or educational projects.

Introduction

Colonists didn’t have hardware stores or modern pigments.

They turned to what grew in their fields or lay near their doorsteps—damp clay, tree bark, garden herbs, even scrap metal.

Those natural dyes and earth pigments did more than cover surfaces.

They signaled faith, rank, trade connections, and a fledgling nation’s identity.

This guide walks you through fourteen essential colonial hues.

Each section begins with a clear introduction to the color’s place in colonial life, followed by three deep dives: Origin, Colonial Use, and Modern Tip.

Whether you’re restoring an old building, crafting a historical costume, or simply curious, you’ll find practical insights and step‑by‑step instructions.

Pilgrim Black

Before diving into the three aspects of Pilgrim Black, let’s understand why this shade mattered:

Black was more than a fashion choice—it was a statement of resourcefulness and humility.

By creating black from local materials, colonists embraced practicality and showed reverence in a faith‑driven society.

Origin

Colonists made black pigment from two affordable sources: burnt wood soot and oak‑gall ink.

Pine knots or pitch‑pine logs burned down to a fine, oily soot.

Separately, oak galls—round growths on oak trees—were crushed and boiled with iron filings.

The iron reacted with tannins in the galls, producing a deep, slate‑black ink.

Both methods required only heat, water, and patience, so even remote villages could brew gallons of pigment without imported supplies.

Colonial Use

Why black? Practicality and piety.

Black hid soot from fireplaces, mud from unpaved streets, and the daily grime of farm work.

It also symbolized modesty in Puritan faith—no bright hues were allowed.

Families prized one good black coat over multiple colored garments.

Wills regularly bequeathed “one good black coat” as a treasured heirloom, akin to a fine piece of furniture.

Modern Tip

To capture Pilgrim Black today, choose a flat, matte black paint or milk paint.

Apply it to stair risers, door frames, or built‑in cabinetry for a quiet, solemn look.

Pair black trim with soft cream walls and natural fiber rugs to echo colonial restraint while keeping interiors inviting.

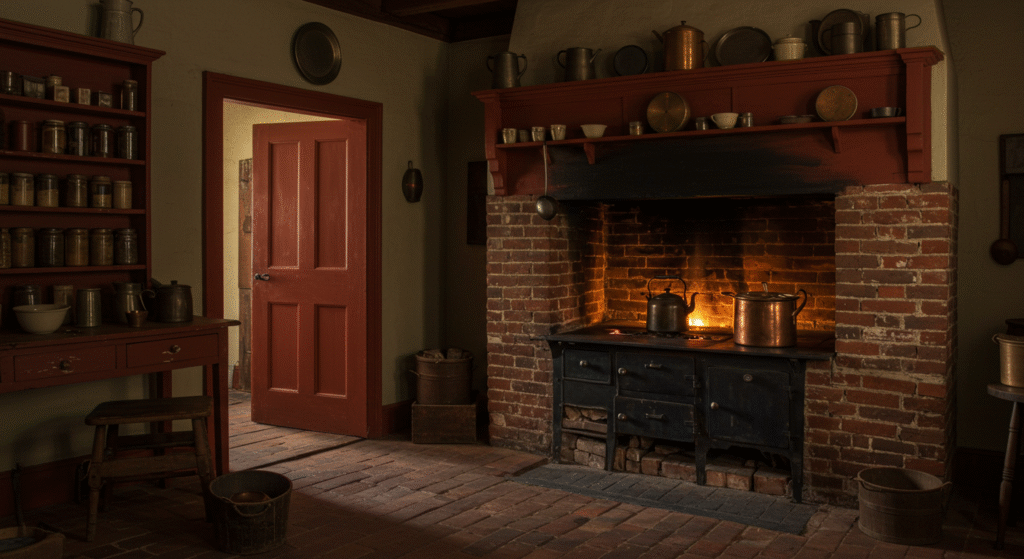

Hearth Red

Hearth Red warmed cold, damp colonial homes before modern heating.

Let’s explore how a simple clay pigment became a staple of early American interiors.

Origin

Early settlers dug iron‑rich clay from creek banks or exposed fields.

After sun‑drying, they ground the clay with stone querns into a fine red powder.

Mixed with water or linseed oil, this pigment penetrated wood pores and baked in place, resisting hearth heat and winter frost.

Colonial Use

This warm red hue brightened entryways, doors, and kitchen tables.

It echoed the glow of the fireplace, making dim rooms feel cozy.

On cabinet doors, spice racks, and door surrounds, Hearth Red added cheer—and hid soot splatters and food stains during long cooking sessions.

Modern Tip

Refresh kitchens or mudrooms with a matte, rusty red paint.

Try a muted barn‑red shade on fixed furniture—like an island or bench—and contrast it with exposed wood floors.

The result feels both historic and welcoming, tying modern décor to colonial comfort.

Madder Crimson

Madder Crimson was prized for its vivid, lasting warmth.

This section explains how a humble plant root transformed garments and ceremonies.

Origin

Madder is a climbing plant whose roots hold alizarin, a potent red dye.

Colonial importers shipped dried root bricks from Dutch merchants to Boston docks.

To dye cloth, settlers first soaked fabric in an alum solution (a mordant).

Then they simmered the cloth with shredded madder root.

Each dip yielded progressively deeper crimson—perfect for sashes and robes.

Colonial Use

Bright crimson sashes marked military officers on foggy battlefields and tavern gatherings.

Town leaders donned crimson robes for public ceremonies, linking red with authority and civic pride.

In some regions, church elders wore dark red stoles during holy days to signal solemn celebration.

Modern Tip

Recreate Madder Crimson at home.

Soak 100% cotton napkins in warm water with alum (found in garden stores).

Simmer them in a covered pot with 2 cups of chopped madder root for 45 minutes.

Rinse in cool water and air‑dry.

Your linens will glow a soft, authentic red—ideal for seasonal table settings.

Harvest Brown

Harvest Brown connected colonists to the earth and fields they tilled.

This intro shows how a by‑product of walnut harvests became a go‑to dye.

Origin

Walnut hulls (the green outer skins) contain high levels of tannin.

Settlers collected hulls during the nut season, then dried them for year‑round dyeing.

Steeping hulls in hot water for hours extracted a rich chocolate‑brown bath.

After dyeing, families dried the spent hulls for firewood—nothing went to waste.

Colonial Use

Farm buildings, tool handles, and woven baskets wore Harvest Brown.

The dark hue masked dirt, soot, and wear, keeping chores from looking messy.

In autumn, brown barns blended into amber fields, blending form and function in rural homesteads.

Modern Tip

Look for a walnut‑hull wood stain or create an herbal dye at home.

Apply it to exposed beams, shelves, or vintage furniture.

Pair with crisp white walls and linen textiles for a balanced, rustic‑chic look.

Amber Wheat

Amber Wheat mixed function with beauty—saving wood and warming spaces.

Here’s how a blend of pine pitch and wax changed colonial floors and trim.

Origin

Colonists heated pine resin (pitch) with beeswax and boiled linseed oil.

They sometimes added a pinch of saffron for extra golden tones.

The hot mixture brushed onto wood filled pores and dried to a hard, golden finish.

It resisted water, foot traffic, and spills.

Colonial Use

Taverns and inns used Amber Wheat varnish on floors to welcome travelers.

The golden sheen reflected candlelight, creating a warm, inviting glow.

On door frames and window sills, the finish protected wood from moisture and wear.

Modern Tip

Try a honey‑tone clear varnish or hardwax oil on wide‑plank floors or trim.

It highlights natural grain and knots, giving rooms an artisanal, lived‑in feel.

Ochre Yellow

Ochre Yellow was a civic color, guiding colonists to public buildings.

This intro shows why a simple earth pigment earned such prominence.

Origin

Yellow ochre is a clay tinted by hydrated iron oxide.

Settlers mined ochre deposits near waterways, crushed the rock, and sun‑dried the powder.

Mixing it with boiled linseed oil or lime produced a buttery yellow paint that sat strong on wood and stone.

Colonial Use

Courthouses, jails, and meetinghouses wore Ochre Yellow trim for visibility.

Travelers recognized the color from a distance, finding public spaces quickly.

Official records from 1745 note funding for fresh yellow paint, calling it essential for clarity.

Modern Tip

Paint porch ceilings, window frames, or built‑in cabinets in a soft ochre.

The hue bounces light in shady spaces and pairs beautifully with slate or red brick.

Verdigris Green

Verdigris Green celebrated colonial copperwork and coastal trade.

This introduction reveals how a metal patina became prized pigment.

Origin

Copper exposed to air and moisture forms a blue‑green crust called verdigris.

Artisans scraped that crust from old copper plates and mixed it with vinegar and straw.

The result: a bright, stable green pigment worth more per pound than many plant dyes.

Colonial Use

Copper cupolas, weathervanes, and clock faces wore Verdigris Green.

In port towns, green roofs guided sailors home.

Luxury goods like decorative boxes and picture frames also carried the hue, signaling wealth.

Modern Tip

Choose a synthetic verdigris paint or aged‑copper finish for small accents—pots, hinges, or light fixtures.

It adds a whisper of maritime history without toxic copper salts.

Sagebrush Green

Sagebrush Green offered early colonists a soft, camouflaged tone straight from the garden.

This intro explains how herb dyes met frontier needs.

Origin

Boiling sage leaves, nettle, and other garden greens with a scrap of iron produced muted gray‑green dye.

Settlers saved seeds for next spring, renewing dye stocks year after year.

Colonial Use

Hunters, trappers, and scouts wore sage‑dyed shirts and trousers to blend into forests.

The color hid in pine woods and scrub, giving an edge to those tracking game—or seeking privacy.

Modern Tip

Paint lower kitchen cabinets, bathroom vanities, or built‑in bookcases in sagebrush green.

The soft, natural hue grounds lighter walls and adds a touch of outdoor calm.

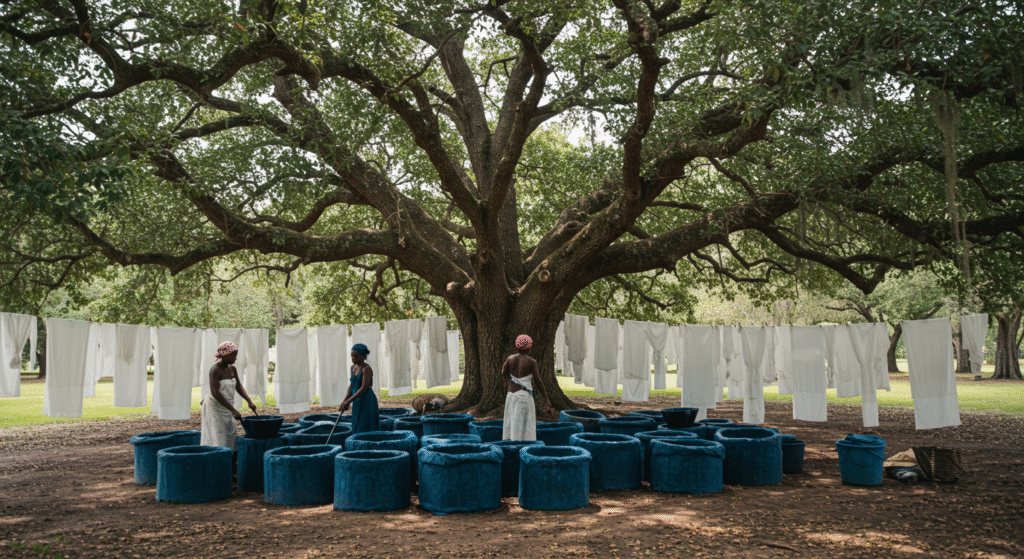

Indigo Blue

Indigo Blue was the crown jewel of colonial dyes, linking plantations to global trade.

This intro outlines its journey from field to fabric.

Origin

Indigofera bushes thrived on southern plantations.

Enslaved workers fermented leaves into thick cakes of indigo paste.

Dyers crushed the cakes, then dipped cloth in lye baths before submerging it in the indigo vat.

With each dip, fabric turned a deeper blue until it resembled the night sky.

Colonial Use

Indigo cloth became a top export and a fashion staple.

Planters paid taxes with indigo cakes, and Boston merchants stocked shelves with indigo‑dyed linen.

Even everyday kerchiefs and work smocks carried a hint of deep blue.

Modern Tip

Opt for upholstery or drapery fabric with visible slubs and thick threads.

The texture mimics hand‑woven indigo cloth, adding authenticity to sofas or curtains.

Woad Blue

Woad Blue reminds us that color economics shifted as rapidly as politics.

This intro covers how a familiar European dye held sway before indigo’s rise.

Origin

Settlers imported woad powder from England.

They mixed it with water and lime, then let the paste ferment.

Once dried into balls, woad powder sat on shelves until a backyard kettle called for it.

Colonial Use

Militia uniforms often started with woad blue—cheap, easy, and locally sourced enough to dye coarse wool.

Some towns banned bright dyes for commoners, leaving woad as the only blue available.

Modern Tip

Select a chalk‑finish paint in a soft slate blue.

Use it on small furniture pieces—chairs, bed frames—to evoke that muted, historic charm without heavy pigment.

Patriot Blue

Patriot Blue became the color of a new country’s hopes and ideals.

This intro shows how a modern pigment left its mark on history.

Origin

Prussian blue, a synthetic pigment invented in Europe, produced the richest, truest blue available.

It mixed cleanly with oil or water, making it perfect for large canvases—like flags.

Colonial Use

In 1777, the Continental Congress specified this deep blue for the new American flag’s canton.

The stars and stripes flew in Prussian blue and madder red, announcing unity and resolve to the world.

Modern Tip

For a subtle nod, paint an accent wall, front door, or kitchen island in a navy close to #0A1F44.

Combine it with bright white trim for crisp contrast and timeless appeal.

Gunmetal Gray

Colonial forges gave us Gunmetal Gray—a practical protective finish for tools and weapons.

This intro lays out the process and purpose behind that utilitarian hue.

Origin

Blacksmiths mixed charcoal dust and iron filings with boiled linseed oil.

They brushed the dark slurry onto wagon wheels, rifles, and plow parts.

Heat from the forge bonded the mixture, creating a rust‑resistant coating.

Colonial Use

A gunmetal‑coated barrel or blade resisted water and mud.

Soldiers and farmers alike depended on the finish to keep gear reliable in rain, snow, and swampy fields.

Modern Tip

Expose metal beams or pipes in open‑plan homes, then seal them with a clear matte varnish.

The natural gray patina shines through, lending an industrial edge rooted in colonial craft.

Snow Whitewash

Snow Whitewash brightened buildings and foiled pests before modern chemicals.

This intro covers why limewash reigned supreme on fences, barns, and churches.

Origin

Crushed limestone slaked with water turned back into lime putty.

Mix a dash of salt, stir into creamy slurry, and roll it onto wood or brick.

As it dried, the lime carbonated back into limestone, locking in place.

Colonial Use

Whitewashed churches gleamed in sunlight, guiding worshipers.

Barns and fences received annual whitewashes to kill mold and deter insects.

The result was breathable, antibacterial surfaces long before sanitizers.

Modern Tip

Refresh picket fences, garden walls, or small sheds with DIY whitewash.

Use hydrated lime from gardening centers, warm water, and table salt.

Roll on, let it dry, and enjoy a bright, natural finish you can renew each season.

Liberty Stripe

Liberty Stripe wove politics into everyday life with bold, tricolor bands.

This intro explains how simple striped fabric became a symbol of allegiance.

Origin

Colonial weavers threaded heavy cotton or linen with alternating red, white, and blue yarns.

They called the sturdy striped cloth “ticking,” using it for mattresses, sacks, and awnings.

Colonial Use

Market stalls flew striped awnings to keep sun off produce and advertise loyalties.

During boycotts, merchants flipped the stripes—blue out—to show support for rebellion, turning everyday shop fronts into political banners.

Modern Tip

Incorporate striped pillows, runners, or upholstery on outdoor furniture.

Choose a narrow band pattern to nod at history without overwhelming your decor.

Conclusion

Colonial colors weren’t mere decoration—they solved problems, told stories, and built community.

By digging into clay, boiling roots, and scraping metal, settlers painted their world with purpose.

Today, you can honor that heritage by choosing palette and process with care—bringing the past into your home or project with authenticity and respect.

Quick Reference Table

| Color | Source | Colonial Use | Modern Hex | Modern Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilgrim Black | Soot, oak-gall ink, iron filings | Clothing, ink | #1B1B1B | Matte black trim or stair risers |

| Hearth Red | Iron-rich clay | Doors, interior woodwork | #7F2A20 | Kitchen island or front door |

| Madder Crimson | Madder root | Officer sashes, robes | #8B2D3B | DIY natural dye for linens |

| Harvest Brown | Walnut hulls | Barn doors, tool handles | #5A4328 | Walnut wood stain |

| Amber Wheat | Pine resin, beeswax, oil | Floor varnish, trim | #C69A5B | Honey-tone varnish on floors |

| Ochre Yellow | Natural ochre clay | Trim on public buildings | #D8A73A | Porch ceiling or shelf backs |

| Verdigris Green | Aged copper patina | Cupolas, weathervanes | #3F7353 | Accent hardware or fixtures |

| Sagebrush Green | Herb dyes (sage, nettle) | Hunting shirts, tents | #79846B | Cabinet bases or bench accents |

| Indigo Blue | Indigofera dye cakes | Clothing, trade exports | #274374 | Denim upholstery |

| Woad Blue | Woad plant powder | Militia uniforms | #4E5E7A | Chalk-finish paint on furniture |

| Patriot Blue | Prussian blue pigment | Flag canton | #0A1F44 | Navy accent wall or door |

| Gunmetal Gray | Forge dust, oil, iron filings | Tool coating, wagon parts | #515154 | Exposed metal sealed clear |

| Snow Whitewash | Slaked lime, water, salt | Fences, barns, churches | #F7F7F2 | DIY whitewash on wood or masonry |

| Liberty Stripe | Red-white-blue ticking fabrics | Awnings, mattresses | n/a | Striped pillows or runners |

FAQ

Q: Why didn’t colonists use synthetic paints?

A: They weren’t invented yet. Settlers relied on what grew in fields or lay near fence lines—clay, plants, and scrap metal. Each pigment offered function and story.

Q: How can I mix these colors myself?

A: Many natural dye and historic paint kits are available online. For do-it-yourself, research safe mordants for plant dyes and follow historic whitewash recipes for lime.

Q: What’s the easiest way to tell whitewash from modern paint?

A: Whitewash soaks in and feels slightly powdery; modern paint sits on top and often peels in sheets.

Q: Which color suits damp climates?

A: Whitewash and amber‑tone finishes resist mold and moisture. They let wood breathe and dry naturally.

Q: What color feels most “colonial” without darkening a room?

A: Ochre Yellow or Hearth Red. They bring warmth and brightness without overpowering a space.

Matthew Mansour, known in the fashion world as a storytelling virtuoso, weaves captivating tales centered around the mesmerizing universe of fashion hues. Possessing a sharp eye for detail, Matthew explores the profound layers of color combinations, turning the simple act of choosing an outfit into a lively adventure. His unique ability to blend emotion and innovation into his writings sets him apart in the sartorial sphere. Each article penned by him carries a touch of magic, inspiring readers to embark on a colorful odyssey through the diverse landscape of apparel shades.

Reviewed By: Joanna Perez and Anna West

Edited By: Lenny Terra

Fact Checked By: Marcella Raskin

Photos Taken or Curated By: Matthew Mansour